More individuals are choosing alternative medicine in their health care, and coincidentally more people are looking to natural and organic alternatives in personal care. The global organic personal care market is expected to grow from $7.6 billion in 2012 to $13.2 billion in 2018, with the United States leading the demand over Japan and Germany.1 The market is only expected to get bigger, but many still question the efficacy of natural and organic ingredients.

Plants were the main source of all cosmetics long before their chemical and synthetic counterparts were discovered to imitate or produce similar qualities. One of the earliest recorded uses of botanical ingredients in skin care dates back to 2600 B.C. in Mesopotamia, where a formula of cypress and myrrh for the treatment of inflammation was inscribed on a clay tablet. Eber’s Papryus, which is dated around 1550 B.C., is one of history’s most important medical volumes. It advocates natural compounds such as henna and wolfberry for their topical antiseptic and healing properties.

In 2001, researchers identified 122 compounds from ethnomedical (traditional medicine practiced by ethnic groups) or pharmacognosy (medicinal drugs from plants) plant sources to create a variety of medications. Nearly 80% of those compounds were used in the same or related manner as their traditional use.2 Pharmacology itself involves ethnopharmacological studies conducted over decades on thousands of species of botanicals, herbs and spices.

Approximately 199 pure chemical substances are extracted from plants and used in the manufacture of medicines throughout the world. The most important extracts with significant activity are then subjected to pharmacological and chemical testing to determine the nature of active components. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 80% of people in developing countries rely on traditional medicine, and about 85% of traditional medicines involve the use of plant extracts.3

Concerns and Regulatory

Bioactive extracts and phytochemicals first act as skin preparations, then influence biological functions second. The effects of these natural ingredients depend on both in vitro (in the glass) and in vivo (in the living) efficacy, in addition to the primary base formulation. However, when using pure plant extracts for skin care, manufacturers must address quality control, consistency and processing methods.

Botanical products are largely unregulated in the United States. Quality control is difficult unless the source is certified. The consistency of a natural extract is a key factor during mass production; microbe counts, residual solvent levels and the absence of pesticides also should be consistent. Extraction and purification methods are also important, as the evaluation of the raw material and finished formula must be sustainable and stable. Studies often are limited with botanicals, and validation is not always supportive.

Many herbal-drug combinations may be of serious concern, and some plants are toxic if used out of scope. Possible photosensitivity, allergic dermatitis, phytodermatitis and other cutaneous manifestations may result. A single reactive event may be interpreted as a “bad botanical experience” and leave a negative connotation no matter the quality of the product. This reaction may have been precipitated by the user’s predisposition to sensitivity, such as dehydration or irritation, or caused by another ingredient in the formula other than the botanical.

No cosmetic product or ingredient is obscured in totality from the development of adverse reactions on the skin, regardless of whether it contains natural or synthetic ingredients. The nature of allergic reactions and skin sensitivities is multifactorial, involving: the skin’s barrier function, prescription medications, the immune system, health conditions, stability and purity of the product, and compliance in individual use. It is simply too vast a task to isolate “culprits” without detailed assessment, evaluation and prudent knowledge of cosmetic chemistry and the monographs involved in the manufacturing of products.

Natural OTC vs. Natural Professional

Typical “natural” OTC products may contain anywhere between 5-70% natural ingredients;4 therefore, making it difficult to evaluate natural efficacy and performance when natural percentage may be high or low. Professional grade products allow for better evaluation of botanicals, with their efficacy based on technology, industry standards and intended quality of ingredients. Botanical cosmeceuticals are particularly interesting, as they have beneficial topical actions and provide protection against degenerative conditions.

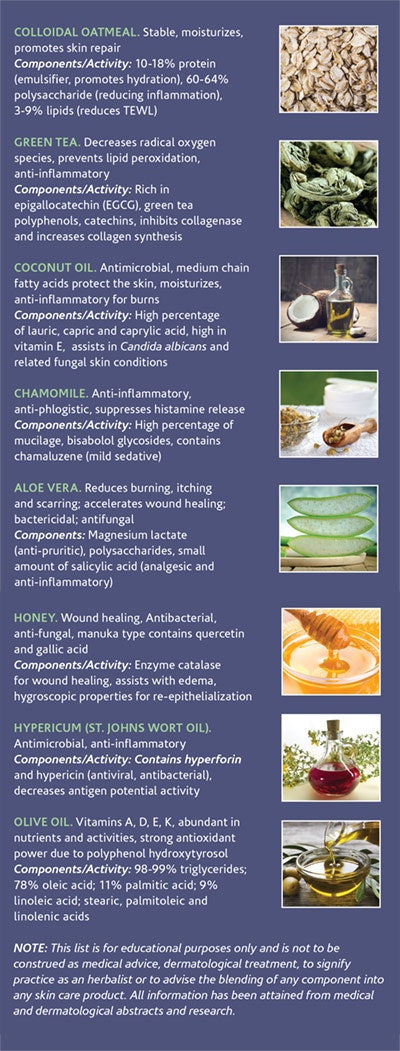

Currently, more than 60 botanicals are marketed robustly in formulations, all for their unique activities as well as performance within a formulation. “According to the number of botanical clinical trials conducted and available, the best evidence exists in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions and diseases, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.”5 Perhaps the most fundamental factor in understanding the interaction between botanicals and skin is to understand the skin’s barrier function, surrounding structures and the metabolic pathways of cells.

Skin Integrity, Inflammation and Sensitivity

Many individuals who experience irritated and inflamed skin such as rosacea and relative conditions seek “natural” alternatives other than medications to hopefully abate symptoms and find relief. From a topical perspective, cosmeceuticals and skin care products with anti-inflammatory ingredients will establish some degree of improvement. However, some may work temporarily, and symptoms may return.

It is important to observe the internal mechanisms of skin inflammation so that herbal skin care is chosen via efficacy and clinical validation rather than an experimental plea in desperation of attaining relief. Additionally, it should be noted that herbal products may also contribute to irritation if improperly selected, used out of compliance by either the technician or the client, not intended for use on the skin, or have not been manufactured under stringent guidelines for safety.

Inflammation of the skin is a complex process that involves a definitive source or antagonist—the release of vasoactivity, histamines, leukotrienes, pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and lymphokines. These antagonists fuel capillary activity that may result in dilation and inflammation. Thus, applying any type of product topically without understanding the mechanism of both the functional and active ingredients and their potential sides effects may negate all worthy intentions. The alteration of the integrity of the stratum corneum via antagonists will be accompanied by a subsequent increase in transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and a decrease in skin hydration factors. Barrier dysfunction is associated with a substantial loss of ceramides from the stratum corneum, which corresponds with TEWL. The aim in management of sensitive skin is to restore the barrier function through the application of ceramides, nutritive lipids and carbohydrates.

Inflammation of the skin is a complex process that involves a definitive source or antagonist—the release of vasoactivity, histamines, leukotrienes, pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and lymphokines. These antagonists fuel capillary activity that may result in dilation and inflammation. Thus, applying any type of product topically without understanding the mechanism of both the functional and active ingredients and their potential sides effects may negate all worthy intentions. The alteration of the integrity of the stratum corneum via antagonists will be accompanied by a subsequent increase in transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and a decrease in skin hydration factors. Barrier dysfunction is associated with a substantial loss of ceramides from the stratum corneum, which corresponds with TEWL. The aim in management of sensitive skin is to restore the barrier function through the application of ceramides, nutritive lipids and carbohydrates.The Power of Plants

The validation of the activity of botanical compounds lies within hundreds of specific phytochemical attributes much in the way essential oils function on human tissue. One plant may possess several characteristics, and various parts of the plant, stems or leaves may interact with the skin differently. Interestingly, botanicals provide almost any type of vehicle including surfactants, oils, butters, waxes and emulsifiers.

Gel polysaccharides (Aloe vera). Some of the most impressive plant compounds cited in countless studies are polysaccharides such as those found in aloe vera gel, which have immunomodulatory properties. Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates found in most plants. They have potent therapeutic benefits and act as demulcents. Demulcents are natural plant skin hydrators and perform distinct barrier function capabilities. This is one of the most impressive natural mediated reactions that plants produce—having an affinity to act in defense of barrier function.

Mucilage (fenugreek). Mucilage containing herbs work similarly to polysaccharides in that they become sticky and “swell” when they come in contact with water. This allows them to act as a “plant bandage,” protecting dry or mildly inflamed skin. Botanicals such as marshmallow, mullein, slippery elm, flax and fenugreek are examples.

Phenolic compounds. These bioactive substances found in plants are actually important constituents of the human diet. They include flavonoids such as anthocyanins, flavonols and flavones, and non-flavonoid classes including phenolic acids, lignins and stilbenes. Botanical and natural antioxidants work by scavenging and inhibiting the propagation of oxidative chain reactions, aiding in oxidative damage repair.6

Phytomolecules (curcumin). Phytomolecules include aloin, ginesenoside, curcumin, epicatechin, asiaticoside, ziyuglycoside I, magnolol, gallic acid, hydroxychavicol, and hydroxycinnamic and hydrobenzoic acid. All scavenge free radicals from skin cells, prevent TEWL, include a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher and protect skin from wrinkles.7

Seek More Information

There are a variety of resources out there for estheticians who want to research and harness the power of plants for skin health. Websites devoted to cataloguing and researching these remarkable natural creations include www.medicinal plants.us, www.herbmed.org and www.herbalgram.org.

Natural or organic product lines often reference science-based websites and chemistry publications for validation of product activity. The esthetician may request technical information from manufacturers to receive accurate information for educating clients. Always ask for scientific support of the skin care benefit provided by your natural and organic product lines, but also conduct research yourself. It can be your most powerful tool in avoiding adverse reactions and ensuring the true skin power of plants.

REFERENCES

- www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/formulating/category/natural/Demand-for-Organic-Beauty-to-Grow-to-Over-13-Billion-by-2018-Report-Says-213160491.html

- DS Fabricant and NR Farnsworth, The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery, Environ Health Perspect 109(Suppl 1) 69–75 (March 2001), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1240543/

- NR Farnsworth, Screening Plants for New Medicines, ch 9 in Biodiversity, EO Wilson and FM Peter, eds, Washington, DC: National Academies Press (1988) www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219315/

- HE Knaggs, Highlights of the 15th Annual Health and Beauty Association meeting: Trends in personal care, New York, USA (Sept 18-20 2007)

- J Reuter, I Merfort and CM Schempp, Botanicals in dermatology: an evidence-based review, Am J Clin Dermatol 11(4) 247-67 (2010), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20509719

- YS Veioglu, G Mazza, L Gao and BD Oomah, Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables and grain Products, J Agric Food Chem 46, 4113-4117 (1998), www.deckerfarm.com/anitoxidant.pdf

- PK Mukherjee, N Maity, NK Nema and BK Sarkar, Bioactive compounds from natural resources against skin aging, Phytomedicine, Dec 15 19(1) 64-73 (2011) www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22115797#

- Botanical Ingredients: Powered by Nature-Proven By Science, Skin and Allergy News, www.edermatologynews.com/fileadmin/content_pdf/supplement_pdf/3v4h78zf_sanews_supplement71.pdf

- MK Bedi and PD Shenefelt, Herbal therapy in dermatology, Archives of Dermatology, 138(2) 232-42 (2002), www.researchgate.net/publication/11516846_Herbal_Therapy_in_Dermatology

- A Peirce, P Fargis and E Scordato, eds, The American Pharmaceutical Association - Practical Guide to Natural Medicines. New York, NY: Stonesong Press Inc. (1999)

- Inflammation & Allergy - Drug Targets, 2014, 13, 168-176 Effect of Botanicals on Inflammation te and Elma D. Baron* Department of Dermatology, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, OH 44106-5028, USA

(All websites accessed Mar 3, 2016)